Two quick notes of warning:

- This entry requires a bit of a European political history lesson, which I'm sure is exactly what you came here for!

- This entry isn't humorous. It's not sad or even introspective, which is how I tend to get when I'm not laughing at myself or other people. It's just an account of a very interesting week during my year at Estaca.

If these two notes don't scare you off, then read on. If history isn't your thing, check back soon and hopefully there will be something more to your liking.

I remember as a teen watching a first season episode of Saturday Night Live in 1975, during which Chevy Chase reported in the Weekend Update segment "Our top story tonight: Generallissimo Francisco Franco is still dead." I also remember having no idea why that was funny to the live audience. If you don't know either, Wikipedia has this to say on the subject:

Franco lingered near death for weeks before dying. On slow news days, United States network television newscasters sometimes noted that Franco was still alive, or not yet dead. The imminent death of Franco was a headline story on the NBC news for a number of weeks prior to his death on November 20.

Giving credit where credit is due, you can find this Wikipedia entry here.

As exciting as that infotainment tidbit was, it wasn't the history lesson to which I referred. On November 22nd, 1975, two days after Franco's death, Juan Carlos was crowned king according to the law of succession promulgated by Franco. In 1978, the Spanish Constitution was changed in a referendum vote to acknowledge Juan Carlos as King of Spain. The Spanish Constitution dictates that the monarch is the head of State and commander in chief of the Spanish Armed Forces.

Try to contain your enthusiasm; we're almost done.

General elections were held in Spain in October of that same year. When the votes were tabulated (with no hanging chads to cloud up the count) the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party, aka Partido Socialista Obrero Español, aka friggin' Commies emerged as the largest party, winning 177 of the 350 seats in the Congress and 157 of the 254 seats in the Spanish Senate.

You can put your History books away now, boy and girls.

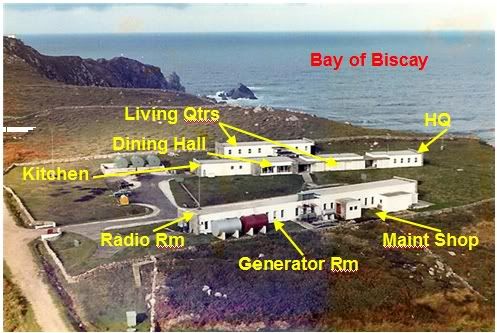

I arrived on site at Estaca in April of 1982 and had no clue about Spain's political structure. Hell, I barely gave a second thought to the American system. For months, life at Estaca was akin to a real life season of television's M*A*S*H series. We played pranks on each other, drank like fish, partied like college kids on spring break, and in our spare time, worked to defend America in our assigned Air Force roles at Operating Location F.

One morning in March of 1983 at the near end of an otherwise uneventful night shift, I heard a strange noise coming from outside the radio building. The equipment rack cooling fans and the industrial air conditioning system in the radio room were very loud. Right outside the radio room door was the generator room and since the generators were the sole source of electrical power for the site, they ran 24/7. Needless to say, the volume level of the rock music from my over sized early 80's era ghetto blaster cassette player was cranked up to sufficiently cover the other noises.

All the other noises notwithstanding, I heard the faint sound of what seemed to be a car horn, so I killed the cassette player and confirmed my suspicion. The radio room had windows, but they were covered on the outside with bricks that had small holes between them. I split the blinds with my fingers and did that move where you adjust your head back and forth, up and down in an attempt to get a composite glimpse of what might be out there. Since there were no fences or gates at Estaca, the occasional tourist would drive onto the site, get out, and take photos. Sometimes, they would park their car, unload the kiddos, and set up a picnic on the grassy knoll near the cliff that dumped onto the Bay of Biscay. We actually once had a couple park in front of the main building, walk into the dining hall, plant themselves at a table, and ask for a menu. But I digress.

|

| View from the Radio Building |

The head bob-and-weave composite image turned out to be an olive drab colored Jeep loaded with bodies. I looked at a radio operator named Mark and he looked back at me, both of us sporting a "what the fuck?" look on our faces as he bolted out the door to see who they were. I found a better vantage point to see what was going on outside and realized that these were not American soldiers. Mark spoke even less Spanish than I did and it was clear by the expression on his face that he had no idea what they wanted from us. He moved himself into the beam of the flood lamp that bathed a small area in light so I that could see him and then gestured towards the window that he and I had previously been peeking through in a motion that indicated that I should stay put. I then watched him turn and walk away and disappear into the darkness in the direction of the main building as the Jeep occupants remained in their vehicle.

Moments later, the intercom phone rang in the radio room. It was Mark on the other end telling me to stay put and NOT to open the door unless I was told to by someone in a leadership role from the site. No one in any leadership role was even awake yet. We agreed on an authenticating phrase and hung up. This phrase would be the confirmation code word for any orders I would be given as long as this ordeal might continue. If I didn't hear the phrase, I could assume that the order was given under duress and as such, would not follow it. To this day, I still have no idea what I would have done in lieu of following an instruction that was not followed by the authentication phrase. I was just the generator guy and I was never briefed on any such potential events. I was only 19 years old. Up to this point, the most stressful event I had faced on site was covering my ass for throwing Molotov cocktails off the cliff at night and having the Spanish Guardia Civil called to the site by a ship who saw the flame bursts on the rocks below. That was a prank and although the "Guads" were not to be messed with (I have a broken nose to show for it, but that's another story), it paled by comparison to what appeared to be happening here.

Daylight broke and there was still no phone call. It seemed as if hours had passed. In fact, they had. To make matters worse, I was hungry and I needed to pee. I peeked out the window again and saw that more military vehicles had arrived. These were personnel carriers and the parking lot was now crawling with soldiers. I looked out to the back of the building through a small crack between the bricks and an exhaust vent that was part of a document incinerator used to dispose of classified documents and the occasional old Playboy or Hustler magazine. The area behind the workshop building was a flowing meadow adorned with and sectioned off by stone walls which stood about three feet high. The meadow stretched out towards the Bay of Biscay with a horizon that kissed the clear blue early spring sky at a seemingly infinite distance. On any given day, it looked like the physical actualization of a painting by Claude Monet. Well, on any clear day, that is. Rainy days at Estaca more resembled a painting by Edvard Munch bathed across a landscape of the Muensters' front yard. Interestingly, the tranquility of the clear pastoral image before me suggested nothing of the turmoil that appeared to be brewing just a few feet away on the other side of the building.

The music had been turned off before Mark exited the shop. Despite the howling of the fans and the blowing of air conditioning equipment, the radio room had an eerie silence about it. I made it a point to stay between the equipment racks, lest any shadows cast by my movement be seen by the soldiers outside. I assumed that as far as they knew, the room was empty when Mark left and that they had no idea what was inside. Finally, mercifully, the intercom phone rang and I almost peed my pants in the shattered silence. I picked up the receiver and listened, saying nothing. "This is MSgt Clark" I heard.

MSgt Clark thought he was God's gift to the enlisted corps. We all just thought he was a dick. (Look for a blog entry on MSgt Clark soon.) "This is Airman Wilson" I replied. "What are you doing in the radio room?" was the next line he spoke. I wasn't supposed to be in there alone, but alone I was and there were procedures to be followed in events such as this. "Follow my instructions implicitly" he began. "I want you to power down two of the radios and kill the alert light". Waiting for an authentication, I didn't reply. He repeated it and then said "Hello?" I heard Mark's voice in the background say "Say tojo".

Tojo (pronounced toe-hoe) is a prickly Spanish plant that has the same effects as bull nettle here in Texas. If you inadvertently brushed unprotected flesh against tojo, it would take weeks for the barbs to work themselves out of your skin. The swelling and resulting rash were miserable and nothing seemed to help. It just took time and you had to wait it out if you got into it. "Tojo" was the authentication phrase Mark and I agreed upon. In hindsight, it seems appropriate. "Tojo" said Clark. "Do that and come back to the phone." I killed the circuit breakers on the racks feeding the radio power supplies, hit the light switch, and went back to the phone saying "Done". The alert light was just a normal white flood light that was positioned on the rooftop corner of the workshop building. It was tilted up so it could be clearly seen from atop a hill and the single lane dirt road that led to the site. The idea was if you were approaching the site and the light was off, something was up - don't continue down. Estaca was a remote unaccompanied tour, but many of us had our wife there. My supervisor even had is three young daughters with him. My wife had been visiting for a few months, but had already returned to Texas awaiting my completion of my year there. The alert light was a simple and discrete warning that could be viewed from a distance sufficient to allow anyone approaching to react and turn around unseen from the site. We once turned it off when Clark was off site hoping he would never come back, but he called the site from a payphone in a restaurant we frequented in Bares. We lied and said it must have burned out. The result was a new, fully documented procedure painstakingly detailing a schedule and process for ensuring the alert light was fully serviceable at all times.

The next order was a little more ominous, but it was kinda fun nevertheless. I was instructed to key up the remaining radio and read the duress code. All mission oriented conversation carried out over the radio was done so using the phonetic alphabet. Each site supporting the Silk Purse mission was issued a set of code books which were valid for a specified amount of time. The codes were essentially sets of three letter combinations that represented a single letter. An example would be FJS=O, VQK=L, BZK=F. If I needed to spell out our site name "OLF",(Operating Location F) I would speak the following phonetic alphabet letters with no discernible pauses as follows:

"Foxtrot Juliet Sierra Victor Oscar Kilo Bravo Zebra Kilo"

Anyone listening in on our frequencies without the code books would be clueless as to the meaning of the spoken letters because the individual letter codes could be comprised of any combination and quantity of letters. I looked up the letters from the code book (which was still out because the previous shift had not ended when Mark left) and wrote out the predefined message on a scrap of paper. I lifted the intercom receiver and Mark answered the other end. "I just want to confirm you want me to do this." Mark, who was a genuine laid back California dude, just said. "Screw it, man! Read it and kill the last radio. TOJO MOTHERFUCKER!" I hung up and read off the letters, which essentially broke radio silence on a predetermined frequency that was monitored back at Torrejon Air Base in Madrid. Interestingly enough, the response that came back in plain English was "Repeat." I repeated the message. I then heard "Is this a joke?"

There was a reason they asked this. Actually, this reason was going to be anther standalone anecdotal entry in the Estaca series, but the details lend themselves well here, so I'll elaborate now.

Every night during a predetermined time slot, each Silk Purse site had to transmit their status to the powers that be in Mildenhall. By the way, the Silk Purse mission objective ceased in 1992 following the collapse of the Soviet Union (thanks to Ronald Reagan), so I'm not divulging anything remotely confidential here. The update process was basically a short message stating the operational condition of the site. Green was all good - all three radios up and running. Yellow indicated one radio down - either for a problem or for routine preventive maintenance. Red meant two radios were down and our ability to support the airborne command post was severely limited. Every night around midnight in their respective time zones, each site would report their status using the phonetic alphabet process described above. A green status message was a short burst of a few letters that when decoded, spelled "green". A yellow message would be somewhat longer to indicate the reason the site was not green. As it was usually just a routine maintenance situation, the message was still relatively short. A red status message required significant elaboration on the part of the site and could take several minutes to code out on paper and then phonetically speak out on the air.

Some paranoid genius way up in the USAFE (US Air Forces Europe) command structure figured out that if the Russians were listening, they would instantly know something was up if a site transmitted a message that was longer than the other messages. Suspecting this, the Commies could focus their resources on that site (assuming they knew where it was) and potentially exploit the presumed weakness. So in their infinite wisdom, someone decided that all messages had to be of the same length. A predetermined number of characters was determined and distributed to each site. Any characters following the actual status were simply filler text. These filler letters could be determined by the radio operator on duty when the message was transmitted. A few months before this incident, one of the Estaca operators sent a status message that was something tantamount to this:

"Green. Abandon search. All occupants dead."

The rest was a recipe for cookies or something, but the rule of a predetermined quantity of letters was adhered to explicitly. Within hours, helicopters from Torrejon Air Base were thundering towards Estaca. The last time a chopper showed up on site it was bringing a visiting General for a morale visit. The idea was that the morale of the staff on site would be boosted because some high ranking officer took the time to fly to the middle of nowhere to visit us. Truth was, the real morale boost came from the helicopter rides the aircrew gave us while the others got a handshake from and a photo taken with the General. The "abandon search" status message generated a helicopter visit with a whole different purpose. Let's just say nobody got a ride, but a few people did get reamed. This incident was my first exposure to the truly bad ass Air Force Pararescue troops. Immediately following what was dubbed "the Estaca incident", a new USAFE Silk Purse policy was enacted that dictated specifically how the filler text would be generated. There were entirely different code books created specifically for this filler text. Another policy was just what we all needed.

Enough of that story. Back to this story.

"Is this a joke?" Before I could reply, another response, this time coded, was spoken. I had to look up the letters and translate their meaning, which was "Is this an exercise?" I suspect the look up process took me much longer than it would have one for of the regular radio guys because Torrejon kept repeating it. I looked up the letters and responded phonetically what translated to "NOT AN EXERCISE." The duress code was a predetermined message of fifty or so letters; very short considering its content. After I repeated "NOT AN EXERCISE" The radio was silent. I waited a few minutes for a response and then killed the power on the last rack. Our phones to other military sites were radio based, so once I killed the line, we were isolated. Estaca was 600 miles from Torrejon. It would be interesting to see the response.

We had a local land line, which we referred to as the "diga phone". When we answer the phone in the States, we usually just say "hello". Spaniards answer the phone "¿Dígame?" (deega-me), which translates roughly to "tell me" or "say to me". I was reminded that the diga phone still worked when it rang and made me nearly wet my pants again. I still had not peed and I was about to burst. If the alert light was off, we were supposed to find a local land line and call the site for instructions, just as Sgt Clark had done months ago. This phone call was another tech calling in as instructed. I told him in as few words as possible not to come on site and that we would reach out to him when it was safe. I emphasized the word "safe".

The radios were off and the duress code was sent. I wondered that was going on. I wondered how long it would take Torrejon to respond. But mostly, I wondered how much longer I would have to wait to pee. I remember feeling an odd sense of separation from everyone. It was odd because the rest of the crew were less than 200 feet away in the main building. We were all taught the basic steps I had just carried out; just in case. But really, what are the odds...? Welcome to my world.

The last step was to destroy the code books. I opened the three ring binder and dumped the pages and my message note sheets into the bottom drawer of the incinerator, which resembled an old metal file cabinet. I slid the drawer shut, spun the combo tumbler, and flipped the switch recessed on the backside of the cabinet. I remember smelling fuel and then hearing a WHOOSH sound as it ignited. Seemingly seconds later, it was silent. I opened the drawer and there was no trace of anything. No ashes; nothing. This sparked an idea (no pun intended). I grabbed several pieces of paper, wadded them up and tossed them in. Then I unzipped my fly, peed on them, closed the drawer, and reignited the incinerator.

I was feeling pretty clever. In my mind, this was space shuttle toilet ingenuity and I was as proud of myself as I was relieved. What I failed to consider was the exhaust from the burned papers. By this time, the Spanish army had spread soldiers all over the place, including the meadows behind the workshop building. A few minutes later, I heard a knock at the door. The knock was only slightly more quiet than the sound of my heart beating in my chest. I walked hesitatingly, daintily between the now silent equipment racks resembling Quai Chang Kaine walking on rice paper as I made my way to the door from the side, avoiding possibly being spotted through the slim crack. I heard Spanish being spoken, but couldn't make it out. Then I heard "Scott! Open up!" I waited' "TOJO! OPEN THE FUCKING DOOR!" It was Mark, Sgt Clark and some Spanish officers.

Mark and Clark (sounds like a morning radio duo, doesn't it) were accompanied by two Spanish officers and Vic, our site cook. Vic was an old local Spaniard who had been the cook at Estaca since it was a US Coast Guard site in the 1960's. Oddly, everyone seemed to be in good spirits. Vic was there to translate. I was officially relieved of my duties, but mostly I was just relieved. I headed across the parking lot/volleyball court to the main building, walked past the Spanish soldier posted at the door as a guard, and made my into the dining hall, joining the rest of the morning crew. "I need a drink!" Vic was busy with our visitors, so breakfast wasn't ready. I made my way into the lounge and poured myself a stiff Coke. I looked over and saw the lock box where the emergency keys to bypass the cipher lock to the radio room were stored. The box had been turned so the latch could not be seen. I suspected that during the incident, someone thoughtfully camouflaged the box and placed shot glasses in front of it.

I went back to my closet of a room and tried to sleep. If the events of the morning weren't enough to keep me awake, the 32 ounces of Coke I slammed down a few minutes before certainly were. I got back up and went back to the dining room hoping breakfast would be ready. I was told to go back and remove my uniform shirt. It occurred to me at that instant none of the American site personnel were wearing anything that indicated military rank. Looking back, I suppose this was a tactical move to keep the "enemy" guessing. I was an Airman 1st Class with only two stripes. I doubt my rank would have neither impressed nor intimidated anyone. Nevertheless, I did as I had done all morning and followed orders. I doffed my shirt and tossed it into the projector room. I was the site's movie night projectionist and had a key.

Breakfast was essentially cancelled that day, so I poured myself a bowl of cereal and choked the milk down. I don't drink milk. I find it peculiar that we as a species drink the milk of another species after we have been weened from our mothers. It doesn't occur naturally with other species in the animal world, so whey do we do it? Yet again I digress.

The staff was abuzz with the events of the morning. There were only nineteen people assigned to Estaca and many of those were off site awaiting an update to return. Still, the buzz was pretty loud. Nobody knew what to do. I went back to my room and cranked up my Screaming For Vengeance album by Judas Priest. Back then, everyone in the Air Force bought a stereo as soon as they could because we got great deals on high end audio gear from the BX. I was no exception. I had massive power and volume with the latest cassette deck and record player technology crammed into my ninety square foot closet of a room. When I jammed, everybody jammed.

I woke up from a catnap and made my way back to the dining hall. When I retired to my closet earlier that morning, I was told our movement was restricted (by us, not them) to the main building until further notice. I looked out the windows and didn't see any helicopters. Darn! No rides. While I was napping, our staff was told by the Spanish officers that their Army had got wind that activities of the ETA (Euskadi Ta Askatasun), the Basque separatists in the region to the northwest of Estaca had raised concern for nearby American military interests. There were several remote Operating Locations throughout Spain. The Basque would routinely hold rallies and we could see them on local Spanish television displaying poster sized maps of US installations and list them as potential targets of action. OL-F (Estaca) was the closest site right under the Basque's noses and yet we never appeared on their maps. Most of the locals always thought we were a weather site, but there was a large group who believed wholeheartedly that the US operated an underground submarine base at Estaca. That was far more exotic than a weather station and some of the single guys on site bragged that the title of Submarine Pilot was far more impressive to the local women than Meteorologist was. Perhaps the Basque leadership discovered we were there and started sabre rattling. The Basque were known to blow stuff up now and then, but were considered rank amateurs back then and even more so by today's standards. Indeed, President Obama's pal Bill Ayers' Weather Underground group posed a greater danger to Americans than did the Basque. In 2010, Basque leader Arnaldo Otegi received a ten year sentence for terrorist actions. Ayers is still out there, albeit in a less threatening role as a retired college professor. In 2011, the Basque announced the cessation of all violent activities.

In the end, all this Basque talk is actually moot because once the helicopters arrived two days later, we learned that the Basque had nothing to do with the actions of the Spanish Army. It turns out that the Air Force restrained and delayed their response because if this was indeed a "just" Basque incident, less attention might be drawn to Estaca if the Basque saw that in the eyes of the Americans, that they (the Basque) (I hoped)) were insignificant and that the incident was small enough to leave up to the locals to resolve.

The real cause of the Spanish Army action was a result of the recent elections and the PSOE gains therein. As you undoubtedly recall from our earlier history lesson, King Juan Carlos held supreme command of all the Spanish military forces. Apparently, high ranking members of these forces were more loyal to the newly established Socialist government than they were to the King. Indeed, sabres were being rattled, but the intent was to demonstrate to the King just who had real command of the Spanish military forces. Why Estaca was chosen for this demonstration was never revealed; not to me at least.

By the end of the first day, the site was literally crawling with Spanish military. Day and night we would hear whistles being blown and and orders barked out in Spanish as the soldiers carried out various basic exercise maneuvers. While we were feeling less threatened by the presence of our "guests", someone on our side decided that we should make living there as inconvenient to them as possible. We made sure all the batteries for the backup lights were fully charged and Vic and his helper moved all the perishable food into a deep freezer. At dusk, we killed the generators and the site went dark. Up to this point, I had never heard what Estaca sounded like without the growl of the generator exhaust echoing off the nearby hills. I remember laying out on the roof of the lounge that night staring at the stars. The starscape at Estaca was indescribably vivid, bright, and contrasted. The stars over there were different than the ones we see in the States. Laying out on that roof day or night was nothing short of therapeutic It was so quiet with the generators off that all I could hear was the Bay of Biscay waves breaking on the rocks a hundred feet below. In fact, the silence allowed me to hear a seagull approaching from a distance. I remember hearing something that sounded like an approaching ffffffffffffffffffffff sound as the gull floated effortlessly above me and it faded away as he flew on. That sound was actually the wind traversing the gull's wings. I never experienced anything like that before or since.

By the time the brass from Torrejon arrived, we had restored power to the site, but not to the radios. For the most part, we were back to life as normal; or as normal as life at Estaca could get, anyway. When the helicopters buzzed over, we were in the middle of a Spain versus US volleyball game on the makeshift court between the main and the workshop buildings. As far as I knew, the Spaniards never entered our living areas or the radio room until the last night when their officers got hammered with us in the lounge. The conversation that night centered around life in America with the most frequently asked question by the Spaniards being who killed JR Ewing.

Throughout the ordeal, I never really felt threatened. It was more of an annoyance,actually and I think I feared pissing my pants and pissing off the Air Force more than I feared the potential actions of the Spanish Army. Seeing the way Spanish soldiers were treated made me appreciate the way the Air Force treated its enlisted men. Until 2001, Spain had a nine month compulsory service requirement for men either in the military or some alternative service. These guys were treated like bastard stepchildren at a family reunion by their leadership. There were times when I felt sorry for myself as a lowly Airman in the middle of nowhere. Those pity parties ceased after the events of that week.

The Air Force brass hung around for a few more days. During their time at Estaca, they shopped the local towns and generally hung out with us, enjoying the sunshine on our secluded beaches and the hospitality of the locals. Before they left, we were debriefed on the events of the week. We were instructed what to say, what to deny, and more importantly, what to forget. After the brass departed, I was issued a Letter of Reprimand by MSgt Clark for being alone in the radio room. Mark was issued one for leaving me there. Had I been the one to greet our Spanish visitors, neither of us would have received our admonishments. A Letter of Reprimand (LOR) was a career advancement killer in the Air Force. I had no Air Force career aspirations whatsoever, but I was devastated by Clark's actions.

I left Estaca the following month, bound for Bergstrom Air Force Base in Austin, Texas. MSgt Clark had gone home to the States on scheduled leave the week following the above described events. He would never return to Estaca. I'll explain why in an upcoming article, but suffice to say here, he got what was coming to him. My LOR was included in my site out-processing documentation package. This was 1983 and the Air Force was woefully behind on administrative computer systems. Remote sites like Estaca still wrote and filed everything manually and any conversions into electronic formats were accomplished at the nearest major installation . While awaiting my processing appointment at Torrejon, I decided to see what all was in my packet. There in the middle of my shot records, relocation orders, and education status forms was the LOR Clark wrote on me. I removed it, wadded it up, and tossed it in the trash. Had I been able to, I would have peed on it and tossed it into the incinerator.

This story has an even better ending. While attending a monthly Commander's Call at my new squadron in the 67th Tactical Reconnaissance Wing at Bergstrom, I was called up on the stage after the general announcements of policy, Airman of the month, etc. The commander, Colonel Corder, pinned an Air Force Commendation Medal on me as I stood at attention, stunned beyond belief. AF Commendation Medals were not common for lowly enlisted personnel during times of peace. In fact, I did some pretty hairy mission oriented stuff during my remaining AF years and never received another one. It may be different now, but in those days, when awards were issued in a formal ceremony, an admin officer would read aloud the citation that accompanied them. The citation would list the specific accomplishments that warranted the award and the signature of the Command Officer who approved it. My citation simply read something like The events and circumstances that warrant the award of the Air Force Commendation Medal to Airman First Class Scott Wilson are classified by [some USAFE order]. Nothing else.

As thrilled as I was to get the award, I was equally perplexed by the fact that it was issued to me for the exact same circumstances for which I was issued a Letter of Reprimand. M*A*S*H had nothing on Estaca De Bares in 1983.